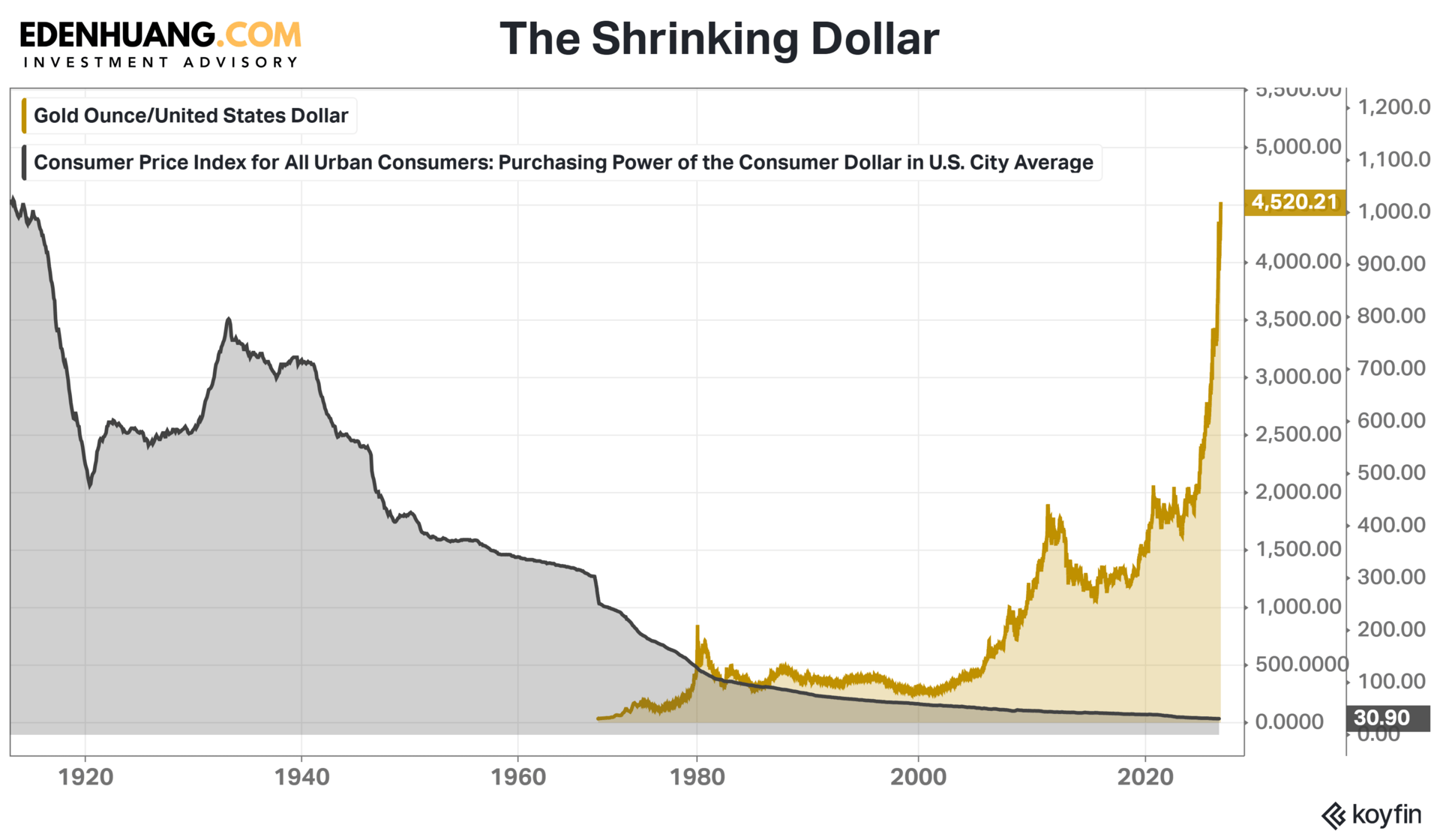

When I look at the following chart, I’m not just analyzing data — I’m remembering moments. I think about my parents stretching every dollar in the 80s and 90s, and how different that dollar feels today. That tiny number, 30.9, hits me and future generations harder than any headline, because it tells a truth we all sense but rarely articulate: a dollar now buys barely 31 cents of what it once did. You don’t need a finance degree to feel that. You see it in your grocery bill, your rent, your kids’ activity fees. Month after month, we’re told inflation is “cooling” or “under control,” yet this line on the chart reveals the real story — a slow, quiet, four‑decade erosion of purchasing power that has reshaped everyday life. And the most striking part is how normal it has all come to feel.

We didn’t wake up one morning and suddenly discover the dollars had shrunk. This happened slowly, almost invisibly, over decades. Every time prices rose a little — a few cents here, a few dollars there — we absorbed it and moved on. But inflation doesn’t reset; it stacks. And decade after decade, those small increases piled on top of each other. Add in rising housing costs, healthcare, education, and the steady expansion of credit and money supply, and you get the world we live in today: a place where a dollar simply doesn’t stretch the way it used to. It wasn’t one crisis or one policy that did it — it was the quiet, compounding effect of many small changes that chipped away at the dollar’s strength until 30.9 became our new reality.

HOW WE GOT HERE: THE MULTI-DECADE SLIDE IN THE DOLLAR’S BUYING POWER

The dollar didn’t collapse overnight. It weakened slowly, quietly, and consistently. We got here because of compounding inflation, expanding money supply, rising essential costs, slower wage growth, credit dependence, global shifts, and the most deceptive of all, policy decisions that favored growth over currency strength, with persistent deficit spending to fund growth and control.

I’ve spent years studying market cycles, but few patterns are as quietly corrosive as America’s addiction to deficit spending. The bottom panel of the above chart lays it bare: year after year, administration after administration, the federal budget bleeds deeper into the red. What began as temporary stimulus in moments of crisis has morphed into a permanent feature of fiscal policy — a structural deficit that no longer waits for recessions to justify itself.

It’s about the long-term consequences of living beyond our means. Persistent deficits mean persistent borrowing. Persistent borrowing means persistent money creation. And persistent money creation means the dollar — the very unit we measure wealth in — loses strength over time. You see it in the CPI line climbing relentlessly. You see it in the purchasing power index falling to 30.9. And you feel it every time your paycheck stretches less than it used to.

Deficits aren’t inherently evil. But when they become the default — when every year is a “special circumstance” — they stop being tools and start being symptoms. Symptoms of a system that prioritizes short-term growth over long-term resilience. Symptoms of a political economy that’s more comfortable printing dollars than making hard choices.

This is why I stress-test portfolios not just against market volatility, but against monetary erosion. Because in a world of persistent deficits, the real risk isn’t price fluctuation — it’s the slow, quiet debasement of the currency itself.

WHEN MONEY LOSES ITS MEANING — THE NEXT INFLATION WAVE WON’T BE GENTLE

Persistent deficit spending and diminishing purchasing power doesn’t just reflect inflation — it quietly fuels it. As each dollar buys less, households feel the squeeze and push for higher wages, businesses raise prices to stay ahead of rising costs, and governments borrow more because their own dollars don’t stretch as far. Investors then demand higher yields to protect themselves from the erosion of real returns, driving up borrowing costs across the economy.

Over time, these pressures feed into one another, embedding inflation into expectations and making the system more sensitive to shocks. When a currency has already weakened as much as the dollar has — down to roughly 31% of its early‑1980s strength — it doesn’t take much for inflation to flare up again. This is how a slow decline in purchasing power becomes the foundation for the next inflation wave.

THE TURNING POINT ALWAYS LOOKS THE SAME: INFLATION RESURGES, YIELDS RISE, AND THE COST OF MONEY FINALLY MATTERS AGAIN

When inflation resurfaces and long‑term yields begin to climb, that’s usually the moment the economic cycle starts to turn. Inflation is the first signal — it tells you that the cost of money is rising and the value of each dollar is slipping.

When inflation rises — or even threatens to rise — long‑term yields don’t stay quiet. Bond markets are forward‑looking. They don’t wait for inflation to show up in the data; they move the moment the risk of future inflation becomes credible. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing now across the G7.

Inflation eats into the real return that bondholders receive. If you lend money at 2% but inflation runs at 3%, you’re effectively losing purchasing power. So investors demand compensation. They push long‑term yields higher to protect themselves from the possibility that today’s “cooling” inflation is just the eye of the storm. Central banks can influence short‑term rates, but long‑term yields are a referendum on credibility — on whether markets believe inflation will truly stay anchored.

Look at what’s happening now: G7 long‑term yields are rising together, almost in formation. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a signal. Markets are quietly pricing in a world where inflation doesn’t glide back to 2% and stay there. They’re pricing in structural pressures — persistent deficits, aging populations, supply‑chain rewiring, energy transitions, and years of easy money that never fully unwound. These forces don’t create a crisis overnight, but they do create an environment where inflation can re‑accelerate faster than policymakers expect.

Rising long‑term yields are the market’s way of saying:

“We see the risk. We’re adjusting before it becomes obvious.”

And when yields rise across the developed world at the same time, it tells you something deeper — that this isn’t a local story. It’s a global repricing of money itself…

FROM SIGNAL TO STRATEGY

At THE MACRO RADAR, we decode the signals. But signals alone don’t protect portfolios. That’s where THE MACRO GPS comes in, translating these signals into actionable allocation strategies.

👉 Clients can keep a Lookout for THE MACRO GPS monthly issue to move from narrative to navigation.

👉 Visit EdenHuang.com to learn how I can help build clarity in a world of uncertainty.

Sincerely,

Assistant Director

Investment Advisory

iFAST Global Markets

Terms of Use & Disclaimers:

“The Macro Radar” and "The Macro GPS" of this newsletter are managed and written by Eden Huang, a representative of iFAST Global Markets, a division under iFAST Financial Pte Ltd.

The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter are those of the writer alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of any affiliated organization.

Views are based on information available at the time of writing and are subject to change as new economic data or market conditions emerge.

Information in this newsletter is intended for educational purposes and does not constitute personalized investment advice.

All materials and contents found in this newsletter should not be considered as an offer or solicitation to deal in any capital market products.

Future expectations outlined in this newsletter are based on available data and reasonable assumptions but are not assured. Economic trends and unforeseen events may alter outcomes.

If uncertain about the suitability of the product financing and/or investment product and/or asset allocation strategies, please seek advice from a licensed investment adviser, before making a decision to use the product financing facility and/or purchase the investment products.

Investment products involve risk, including the possible loss of the principal amount invested. Past performance is not indicative of future performance and yields may not be guaranteed.

While we try to provide accurate and timely information, there may be inadvertent omissions, inaccuracies, and typographical errors.

iFAST Global Markets: Terms and Conditions

This newsletter has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.